Call it superstition, but I’ll take the stairs to the Pulmonary Function Lab every time—even if they move it up a level each year. Okay, that’s only happened once, and now the remaining stairs lead to the roof. They probably won’t add a story to this 116-year-old building.

I arrive breathless and sweaty to check in on the 6th floor. To my right, a couple sits in chairs with their backs to the floor-to-ceiling windows. Light rain mists the glass, clouds obscuring the Golden Gate Bridge. It’s August 3rd. I remember someone on Instagram trying to make “FOGUST” happen. Starts to make sense.

Two out of three others in the waiting room aren’t wearing masks. Insane, I think. I spell my last name for the receptionist, still winded. It occurs to me that anyone listening might assume I’m very sick, rather than in the process of working my heart rate up for a spirometry. Hopefully, they’re worried I’ve got something contagious. I smirk, unnecessarily trying to suppress it under my N95.

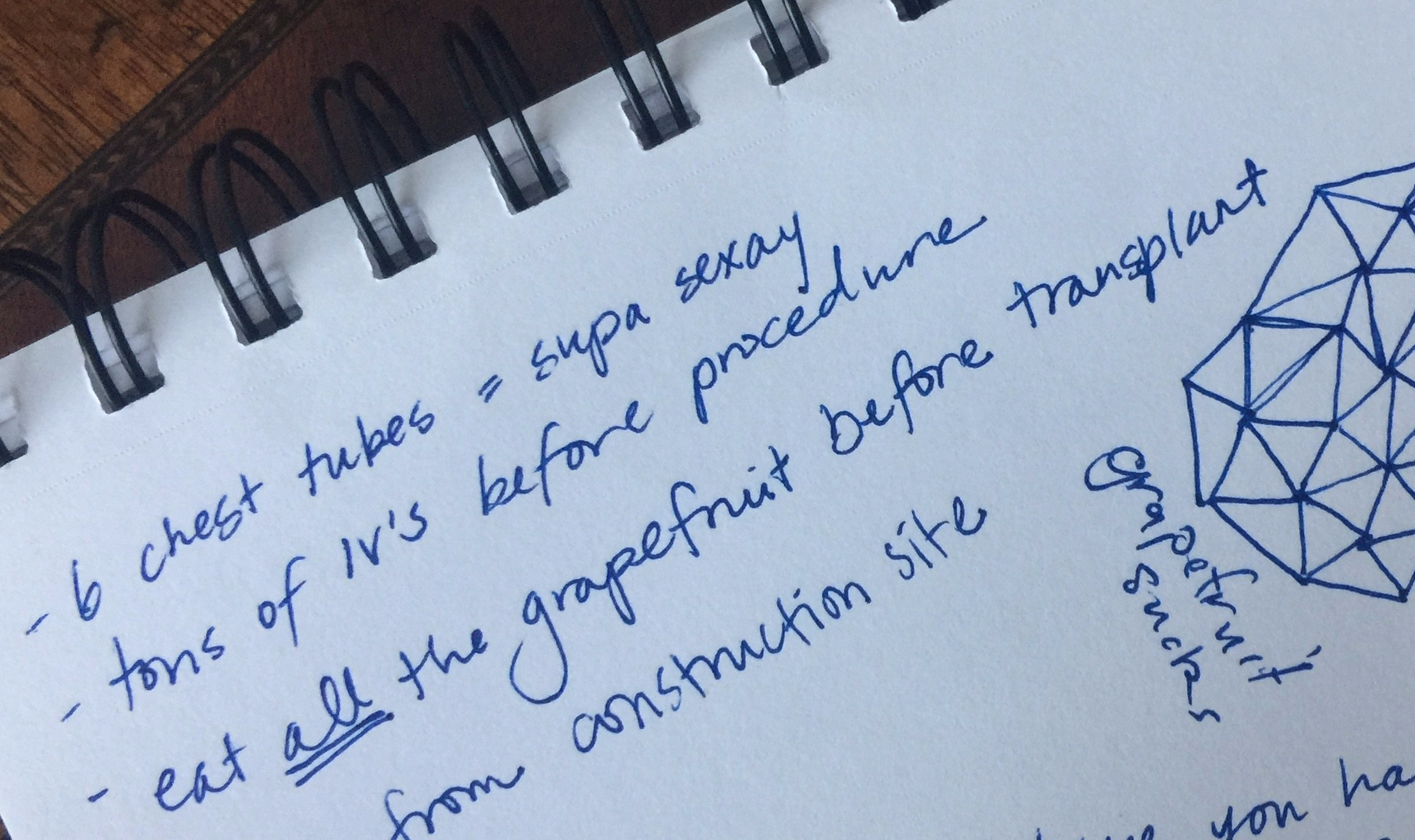

During a heart transplant operation (or heart-lung transplant in my case), the vagus nerve gets damaged, or “denervated.” Instead of getting a signal from my brain to increase cardiac output, my denervated heart stays at a sleepy pace close to my resting heart rate for the first few minutes of exercise. My heart relies on backup mechanisms, including hormone responses, to increase output.1

I have no real evidence that getting to a heart rate suitable for exercise will help me exhale more air, and therefore “score” higher on the test, but it kinda makes sense, right? And anyway, it can’t hurt to get some stair-climbing in. I’ve got a wedding to get in shape for, after all!

Later I meet a new attending physician who tells me BMI affects the score: “Not saying you need to lose weight, but…” Loud and clear, Doc. I guess we’re having a salad for dinner again tonight. (Don’t get me wrong: I’m in, as long as there’s ample bread and cheese involved, like in this New York Times recipe).

Is this a food blog now? Maybe. Traditional Caesar salad dressing contains raw egg yolks, making it risky for me to consume given my suppressed immune system. This is a delicious alternative! I’m not vegan so I typically add some parmesan, but nutritional yeast works great, and I always include it in the dressing for extra folate.2

The Pulmonary Function Test is the gold standard to check for rejection or infection. I beat my score from January by a hair, most certainly within the margin of error. I’ve had COVID-19 between the two tests so I’ll take it. The rest of the day continues with more confirmation that I’m “doing awesome.” Keep it up. No changes. I’m not sure I’ll ever get completely used to this after spending the majority of my life on a declining health trajectory.

On the walk home, I think of my friend, Isa, who recently died after cancer moved into her transplanted lungs. So not fair. I’m lucky to feel as well as I do today. Lucky number seven…what will this eighth year post-transplant bring, I wonder.

Breathing deeply, I slow the racing thoughts in my head, trying not to project into the future. Everyone’s journey is different, they tell us. And yet, living 19 years post-transplant sounds like a great run I’d like a shot at. Historically, only a little over 30 percent of lung and heart-lung transplant recipients survive 10 years or more.3 I simultaneously feel like she was short-changed, and hope at my core that someday Isa’s miraculous longevity is not the outlier it is today.

Kendra’s voice pipes through my AirPods and covers me in goosebumps. Last week she told me how much she misses Bunnie—her personality and the way she saw the world. Bunnie died in April, just 18 months after her heart-lung transplant. Profound (if brief) friendships define post-transplant life.

Between wedding dress try-ons I get an overdue DEXA scan. Fortunately, that finds my bone density relatively unchanged since I began a 2-year “drug holiday” (not as fun as it sounds). When I was transplanted, I took a few different medications aimed at recovering what prednisone4 leaches from my bones. A couple years ago we discontinued those to stave off the negative side effects caused by long-term use of these medications. Because of course there are negative side effects from long-term use of the medications used to combat the negative side effects of long-term use of other medications.

Pharmaceutical absurdity aside, I’m thrilled to be in the normal range for my age. This 30-year-old body better not fall apart before my 61-year-old heart and lungs do. No doubt seven years of weight-bearing exercise has helped. I force myself out for another neighborhood walk.

My mom calls me just to reflect on how wild it is that she bought me a wedding dress. We didn’t dare to dream about this when I was growing up. (And no, not just because of my disposition). I don’t take for granted that I am planning a wedding with my wonderful fiancé, Chase. That we booked a photographer 16 months in advance. That we sent out save-the-date cards a year in advance. That I have almost zero anxiety about needing to reschedule it for health reasons.

Naturally, I contrast my plans for 2024 with my inability to plan in 2015, when I started working as an event photographer. I tried not to accept any gigs more than a couple months in advance because I simply could not count on being healthy and energetic enough to work, let alone home rather than hospitalized.

In fact, I had to find more substitute shooters in the first year of my career than in the subsequent seven years combined. Consistent stability empowers me to plan to dance all night in the mountains at 7,000 ft elevation! I desperately grasp at these wisps of control over my own life.

Of course I recognize nothing is guaranteed, and of course it’s not just stable health that makes the next steps in my life possible. It’s having the courage—the audacity, even—to plan on having stable health next year, too. Another muscle I’m building for the first time in my life.

As Chase says almost daily: Life is good. As he says only slightly less frequently: Worst case scenario, Putin blows us all up. Gotta keep things in perspective.

- Awad, “Early Denervation.” ↩︎

- Folate (vitamin B-9) is important in red blood cell formation and for healthy cell growth and function. ↩︎

- Yusen, “Primary Diagnostic Indications,” 6.

↩︎ - Prednisone is a corticosteroid I take to prevent rejection of my transplanted organs. Long-term use can lead to myriad side effects, including thinning bones (osteoporosis). ↩︎